Koplopers Nederland Waterstofland

Het Nederlands bedrijfsleven kiest voor het versnellen van de waterstofeconomie. Voor de werkgelegenheid, voor de economie én voor het klimaat.

Meer dan 80 Nederlandse bedrijven hebben de handen ineengeslagen en zich verenigd in de gelegenheidscoalitie Koplopers Nederland Waterstofland. De coalitie bestaat uit bedrijven uit de hele waterstofketen én daarbuiten: producenten, industrie, mobiliteit, techniek en advies. Van innovatieve startups tot grote multinationals, zij formuleerden elk een individueel commitment. De verzameling hiervan ligt nu voor u, het ‘Waterstof-commitments Bidbook’.

Een boek vol toewijding, concrete plannen, projecten en investeringen om te laten zien dat het bedrijfsleven van waterstof in Nederland een succes gaat maken.

Het bidbook toont een uniek overzicht van nieuwe waterstofprojecten en concrete plannen van bedrijven:

• Dieselaggregaten en machines op aardgas worden in dit bidbook omgebouwd tot mini-elektrolysers, waterstofaggregaten en -machines. In te zetten bij festivals, bouwprojecten, op campings, in fabrieken van koekjes, brood en meer. Alles plug and play.

• Bedrijven die hun schepen, vrachtwagens, zware bedrijfswagens en personenauto’s willen vervangen voor transport op waterstof; bedrijven die deze voertuigen leveren én bedrijven die de tankinfrastructuur hiervoor aanleggen en de waterstof leveren;

• De aanleg en aanpassing van offshore windparken, van grootschalige ondergrondse infrastructuur en specifieke installaties bovengronds. Van wind op zee naar waterstofgebruik achter de voordeur van een industriebedrijf of woning;

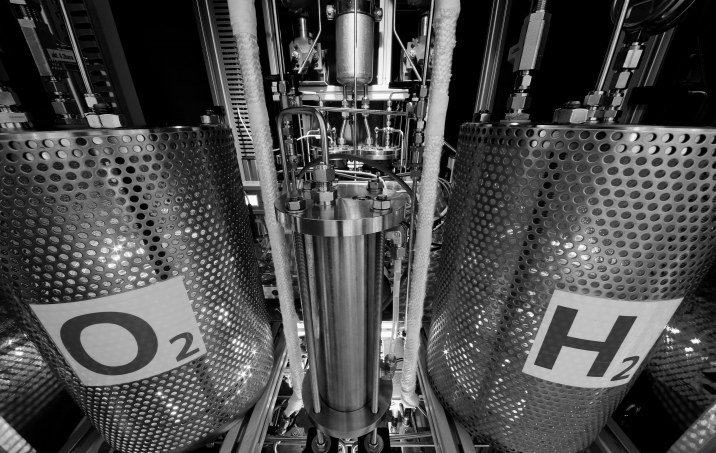

• De bouw van waterstoffabrieken en elektrolysers bij industrie- en chemiebedrijven om in de toekomst de CO2-uitstoot te verminderen.

Handreiking en oproep aan de overheid

Tegelijkertijd is dit Bidbook concrete handreiking en oproep aan de overheid als onmisbare schakel in de waterstofketen: willen we niet achteropraken bij onze economische en klimaatdoelen en bij de ontwikkelingen van de landen om ons heen, dan moeten we nu opschalen aan zowel de vraag als de aanbodkant. Laten we gezamenlijk aan de slag gaan. We hebben alles in huis: de kennis, ervaring, ligging én bedrijven. Samen maken we Nederland Waterstofland!

Namens de Missie H2 initiatiefnemers, Gasunie, Toyota (Louwman Group), Groningen Seaports, Remeha, Shell, Stedin Groep en Port of Amsterdam

Koplopers Nederland Waterstofland

Wienerberger Annual Report contribution

Tailwind for Hydrogen. Hydrogen – a substance with a future

“THERE IS NO ALTERNATIVE TO GREEN HYDROGEN”

Professor van Wijk, green hydrogen is regarded as the key to the energy system of the future. What is it that makes this gas so special?

Van Wijk: There are two main reasons why green hydrogen is important. First of all, renewable energies are normally produced in regions where demand is low. Take the example of offshore wind parks. Hydrogen is an excellent and inexpensive storage medium for the transport of electricity to consumers around the world. It can also be imported at low cost. Second, green hydrogen can be used directly, for instance as truck fuel, in industrial processes, and to heat buildings.

Transport, industry, buildings: Green hydrogen is used for decarbonization in many areas. Where do you see its greatest potential?

Van Wijk: There is great potential in all these areas: For example, if processes in the chemical industry are to be decarbonized, there is no alternative to green hydrogen, be it for the produc- tion of fertilizer or plastics. Interesting projects have also been launched in the steel industry. In Austria, for example, hydrogen is used in steel production.

Which role do you think green hydrogen will play in achieving the EU’s climate neutrality target by 2050 and the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement?

Van Wijk: By 2050, green hydrogen must have become an essential part of the energy mix, which I think will consist of 50% electricity, mainly from solar and wind power, and 50% hy- drogen. We must not forget that green hydrogen is produced from clean electricity. The energy system will be electricity-based, but part of the renewable energy will be converted into hydrogen for transport and storage reasons.

A massive increase in the use of green hydrogen is part of the EU’s strategic vision. What needs to be done to reach this goal?

Van Wijk: Currently, hydrogen accounts for 2% of the global energy consumption. The primary sources of energy are fossil fuels, such as natural gas. However, things are beginning to change. Five years ago, nobody would have thought that we would be able to transport renewable energy all over the world, simply because it was so expensive to produce. Today, the cost of solar and wind energy has decreased drastically. On average, the most cost-efficient options are roughly between 1 and 2 cents per kilowatt hour. This is the reason why green energy is becoming more and more relevant.

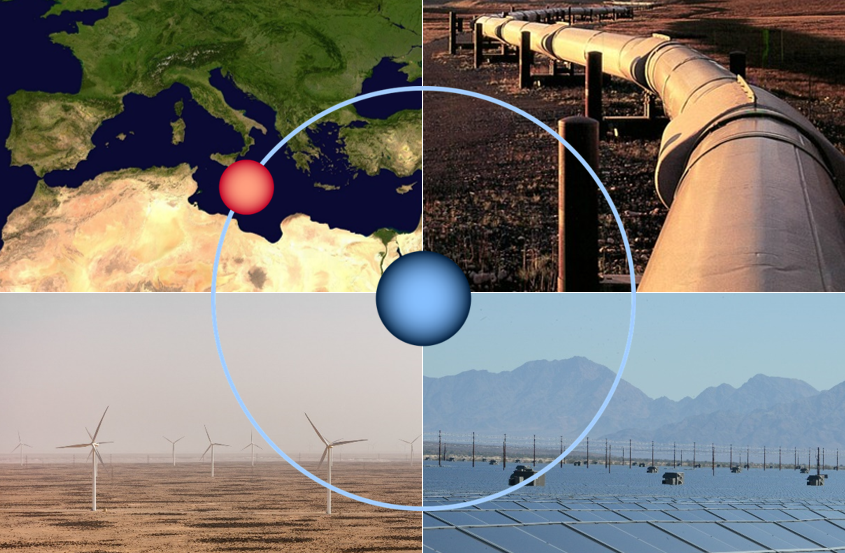

Now the time has come for the next step: There are regions on this planet, such as the Sahara Desert, that have enormous potential for renewable energy. This resource must be tapped in the coming years. We have to abandon the idea of generating renewable energy solely in our immediate environment.

What will be needed in the upcoming years in terms of political conditions and technological developments?

Van Wijk: As a professor at a university of technology, I can tell you that the necessary tech- nology has already existed for 100 years. However, electrolyzers are currently being used for the production of chlorine from salt dissolved in water. We have to adapt them specifically for hydrogen production. And we have to convert the existing natural-gas infrastructure to an in- frastructure for hydrogen. That’s not something a company can do; it’s a task to be taken on by governments. Now is the time to do it, given the need to stimulate the economy after the Covid-19 pandemic.

What is your personal vision of the energy system of the future? What are your hopes and expectations?

Van Wijk: We still have great challenges ahead of us. I am currently involved in the European Union’s work on hydrogen legislation. If we deal with hydrogen merely in a subparagraph of major energy regulations, there will never be a system change. Apart from the energy targets, we also have to bear in mind the opportunities offered by green hydrogen. For example, step- ping up the production of hydrogen in Northern Africa will create jobs and generate economic growth. This could be a way to reduce emigration from that region. Europe, for its part, has the potential to become the global leader in industrial electrolysis. If we succeed in creating the appropriate political framework for these developments, a sustainable energy future will come within reach.

https://www.wienerberger.com/en/annual-report.html#!/en/WkMlnB9q/tailwind-for-hydrogen/?page=1

De 10 Waterstof / the 10 hydrogen commitments

De 10 waterstof commitments van Nederland

- Wij zullen waterstof liefhebben gelijk wij ook elektriciteit lief hebben.

- Wij zullen onze bedrijven én consumenten toegang en recht geven op waterstof.

- Wij zullen schone waterstof gelijk behandelen naar gelijke koolstofinhoud.

- Wij zullen onze windrijke wateren ruimhartig openstellen voor grootschalige waterstofproductie .

- Wij zullen, zonder onderscheid van herkomst, schone waterstofimport ten volle stimuleren.

- Wij zullen onze gasinfrastructuur, opslagfaciliteiten, tankinfrastructuur en havenfaciliteiten ruimhartig

en spoedig geschikt maken voor waterstof. - Wij zullen onze elektriciteit- en waterstofsysteem intelligent koppelen teneinde eenieder altijd en

overal van schone energie te kunnen voorzien. - Wij zullen het toepassen van schone waterstof voor iedereen bespoedigen en stimuleren via belonen

en beprijzen, via quota en caps. - Wij zullen schone waterstof productie, transport, vraag, innovatie en bedrijvigheid ruimhartig

financieel ondersteunen voor een schone, gezonde en krachtige economie, werkgelegenheid, milieu

en leefomgeving. - Wij zullen ons gezag doen gelden om zo spoedig mogelijk waterstof wettelijk te verankeren en de

transitie naar waterstof voortvarend te regiseren.

English

- We shall love hydrogen as we love electricity.

- We shall give our companies and consumers access and rights to hydrogen.

- We shall treat clean hydrogen equally according to equal carbon content.

- We shall generously open our windy waters to large-scale hydrogen production.

- We shall, without distinction of origin, fully stimulate clean hydrogen imports.

- We shall generously and soon make our gas infrastructure, storage facilities, fuelling infrastructure

and harbour facilities suitable for hydrogen. - We shall intelligently link our electricity and hydrogen system in order to provide everyone with clean

energy anytime, anywhere. - We shall accelerate and stimulate the application of clean hydrogen for everyone through rewards

and pricing, through quota and caps. - We shall generously financially support clean hydrogen production, transport, demand, innovation

and business for a clean, healthy and powerful economy, employment, nature and living

environment. - We shall exercise our authority to legally anchor hydrogen as soon as possible and energetically

direct the transition to hydrogen.

Mini-college over waterstof

Why Green Hydrogen? AFSIA Green Hydrogen in Africa E-conference

Download the entire presentation.

Koplopers Nederland Waterstofland

Webinar Veilige Energietransitie: Waterstof

Tijdens de webinar nam lector Energie- en transportveiligheid Nils Rosmuller samen met een aantal gasten de kijkers in anderhalf uur mee. Ad van Wijk van de TU Delft nam de kijkers mee in de grote lijn van energietransitie in Nederland, en de cruciale rol van waterstof als transport- en opslagmedium daarin. Bart Vogelzang van Alliander maakte duidelijk op welke wijze waterstof getransporteerd en gedistribueerd wordt, en vertelde welke veiligheidsaspecten daaraan verbonden zijn. Projectmanager Wim Hazenberg van Stork ging vervolgens in op het gebruik van waterstof in de gebouwde omgeving. Tot slot vertelden Dirk van Dijken en Niels Westra van Veiligheidsregio Drenthe hoe ze in hun regio vanuit risicobeheersing te werk gaan, nu er een complete wijk op waterstof wordt aangesloten. De webinar werd afgesloten met een paneldiscussie met alle deskundigen. Ook werden er vragen beantwoord in de chat.

Verbindende rol

“‘We willen bekendheid geven aan nieuwe vormen van energie. Daarom maken we deze serie van minicolleges om verschillende partijen kennis te geven over welke rol zij hebben en wat het betekent voor de veiligheid. Juist door de verschillende betrokken partners met elkaar te verbinden en met elkaar in gesprek te gaan over de veiligheidsaspecten in verschillende schakels van de waterstofketen, kunnen we grote stappen voorwaarts zetten”, vertelt Rosmuller.

The race for green hydrogen

Large swaths of low-cost land: check. Lots of sun and wind: check. The ability to transport green hydrogen cost-effectively to energy importing economies: check. Then you’re in the race to become one of the “renewable energy superpowers” of the low-carbon economy. A growing number of countries are assessing their renewable resources and natural attributes and positioning themselves to become green hydrogen exporters. However, not all are created equal. FEBRUARY 13, 2021 BLAKE MATICH

Chilean President Sebastián Piñera has set his country the ambitious target of becoming a world-leading hydrogen producer by 2030.

Image: Gobierno de Chile

From pv magazine 02/2021

In light of green hydrogen’s potential and the geopolitical prospectus of the 21st Century, a question arises: would the sun have set on the British Empire if it had been covered in solar panels? This is to say, if green hydrogen is going to power this century forward, which nation or nations will possess that power? Those with the key resources of solar and wind must now be engaged in a geopolitical race for that power both literal, economic and political.

Of course, fossil fuels can also be used to generate hydrogen. However, as Professor Ad van Wijk of TU Delft in the Netherlands explains, costs of green hydrogen are likely to fall. “If you can produce electricity for US$0.01-0.02/kWh, and in solar there are good signs already… then you can produce for $1.50-2.00/kg.” At that price green hydrogen produced by solar and wind will out-compete gray and blue hydrogen.

Major actors

Goldman Sachs has called green hydrogen a “once-in-a-generation opportunity” that it estimates “could give rise to a €10 trillion addressable market globally by 2050 for the utilities industry alone.” Given such economic potential, realpolitik tells us that, like nuclear weapons, whoever lacks a foothold in the green hydrogen economy is at a significant geopolitical disadvantage. But, just as the United States had the scientists in WWII, it is the countries with the right resources, infrastructure, and entrepreneurial zeal, that have the distinct advantage in the race for green hydrogen.

Many nations are rich in solar and wind resources, fewer possess the other requirements alongside. According to Nadim Chaudhry, CEO of World Hydrogen Leaders, an online platform of industry executives designed to accelerate the production and distribution of clean hydrogen, the leaders in the geopolitical race for green hydrogen are Australia, Saudi Arabia, and the North Sea nations – the Netherlands in particular.

“Specifically, Australia” says Chaudhry, “for the sheer size of the proposed projects, political support, robust financial system with a low weighted average cost of capital, a strong body of entrepreneurs and the asset maximizing combination of wind and solar in say the Western Australian project of Infinite Blue Energy.” That project being the 26 GW Asian Renewable Energy Hub (AREH) in the Pilbara region of Western Australia (WA).

The AREH is not the only significant green hydrogen project in Australia, nor even in Western Australia, nor even in the Pilbara region. Proposals for green hydrogen plants are becoming commonplace in sunburnt and windswept Australia. In large part this is due to the interest of trading partners, particularly Japan and South Korea, but even a nation as far distant as Germany has joined Australia in a feasibility study for a supply chain.

Of course, there are countries far closer to Europe with similar resources, state-led economies such as Algeria, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia. However, Chaudhry suggests “they may lack the entrepreneurial pace of what is happening in Australia.” Like Van Wijk, Chaudhry says that it is a “race to scale and the costs of transport.” Green ammonia could prove a cost-effective energy vector in this regard, allowing a nation as far afield as Australia to reach extra-regional partners. Although, in the long term “Australia would lose any first mover advantage …There is lots of land in North Africa and four existing methane pipelines connecting Africa to Europe.”

Of course, we cannot forget the giant red dragon in the room. As Marius Foss, Head of Global Energy Systems at Rystad Energy explained, China are a race leader too thanks to “their willingness to invest heavily”, particularly in electrolyzers which Foss likens to solar manufacturing.

Citing Wright’s Law, Foss says that it’s “simply a volume game where the one that produces the most becomes the most competitive.” However, Foss also noted that if, as we are seeing in the battery space today, the United States and Europe develop “a willingness to pay a premium to get locally sourced components,” then China’s comparative advantage could deteriorate.

Bit parts

Given the logistics of transportation from resource rich areas to population hubs, it is hard to see the green hydrogen economy becoming monopolized anytime soon. As IDTechEX Energy Storage/Hydrogen Technology analyst, Daniele Gatti, told pv magazine: “Adopting a hydrogen economy means developing the entire supply chain: production, transportation and distribution, and also its consumption.”

Even Australia then, a big fish at this point, will ultimately have to settle for being a big fish in a regional pond – the Asia Pacific. “Australia will mainly have Japan, China, South Korea … as their home markets,” said Van Wijk. The world will be divided into regional markets of “cheap hydrogen where there will be competition purely on cost basis.” In Asia, for instance, Australia will compete with Saudi Arabia and Oman.

In a regional geopolitical landscape, there’s great potential for bit parts to play significant roles. Take Chile for example, in November 2020 President Sebastian Pinera set his government the ambitious goal of becoming one of the world’s leading exporters of green hydrogen by 2030.

According to S&P Global, President Pinera believes his country’s record solar irradiation levels mean it could become the world’s most efficient producer of green hydrogen, “more than compensating for the country’s distance from major markets.” However, considering the price of solar and wind will continue to drop across the board, in the long run Chile’s solar efficiency advantage wouldn’t obviate the transport costs incurred in its distance from major markets. In the end, Chile will be a big long fish in the American pond.

Among Chile’s green hydrogen competition in the Americas will be Canada. The Great White North has significant hydro and geothermal power. Such resources will not be able to compete for major market share with solar and wind but countries like Canada and Iceland can certainly produce green hydrogen cheaply.

This is not to forget the giant, until recently orange, dragon in the room, the United States. As Van Wijk pointed out, not even the Trump Administration attempted to diminish the growth of hydrogen. “And why was that?” he asked rhetorically, “Because you can also produce hydrogen from coal and natural gas.” Though it is hard to see the Biden Administration continuing in that vein, the United States suffers under the same transport costs as everyone else, and due to its natural gas reserves, like Russia, it will likely proceed with hybridized hydrogen for the foreseeable future.

Some potential dark horses in the geopolitical race for the green hydrogen economy, particularly from a European perspective, are Portugal and the Ukraine. “We have been impressed with the Portuguese government’s grasp of the hydrogen opportunity,” said Chaudhry, and “the other dark horse is Ukraine, which has good solar and wind resources, pipelines into Europe and a vested political interest in becoming resource independent.”

Death throes

Green hydrogen may be the talk of the town, but grey, blue, and even “turquoise” hydrogen still make up a good amount of the talk that’s going on behind closed doors. Many nations will be unwilling to commit to green hydrogen, some lack the resources, some the infrastructure, some the political or entrepreneurial will, and some are waiting, perhaps greedily, for more immediate incentives from trading partners and the market. “There is difference all around the world,” said Van Wijk, “of where the hydrogen will come from.”

For this reason, many nations will adopt the hybridized approach. Take Kazakhstan for instance, it is a nation the size of Europe with enormous resources, particularly wind and natural gas. Kazakhstan’s central location on the Eurasian landmass makes it ideally situated to export to export to hydrogen hungry nations in both Europe and Asia. Moreover, as Van Wijk points out, Kazakhstan is already venous with pipelines that can be used to transport their gray-green hydrogen.

In the end though, as Van Wijk is unafraid to declare, solar and wind will win out. Fossil fuels will simply fail to compete for price on the global market as the century rolls on with sun beating and wind chiming. “I’m not so afraid,” say Van Wijk “in the end solar and wind will out-compete.”

In the interim, the play of these opposites, renewables and non-renewables, future energies and “traditional” energy sources, will ensure a dynamic geopolitical scramble. While future generations will scoff derisively at the idea that fossil fuels could ever be deemed more “traditional’” than sun, wind, and water, living generations know that some traditions die hard.

Nevertheless, this scramble for the green hydrogen economy looks set to play out on a global scale between resource-rich nations with existing infrastructure, before the race devolves into regional markets wherein those who have solar and wind will compete for exports to neighbours who have not.